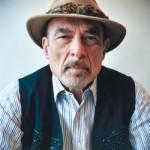

Dr Irvin D Yalom, Professor Emeritus of Psychiatry at Stanford University has been inspiring and training psychotherapists for over 50 years as well as captivating audiences with his rich and compelling tales of psychotherapy.

His text books Existential Psychotherapy and The Theory and Practice of Group Psychotherapy, have inspired generations of therapists. Dr Yalom’s fiction and non-fiction books contain psychotherapy themes at their core and have been embraced by readers across the world.

Dr Yalom’s latest book Creatures of a Day: And Other Tales of Psychotherapy is a moving and poignant collection of tales from psychotherapy. In these stories Dr Yalom shares how his patients grapple with life’s greatest challenges of taking responsible for leading a life worth living and facing imminent death.

Australia Counselling was honoured to have the opportunity to interview Dr Yalom about his latest book and other topics related to psychotherapy.

In this interview Dr Yalom discusses:

- Writing and psychotherapy: The relationship between his creative writing and psychotherapy.

- Therapist disclosure: Why he sees therapist disclosure at the centre of effective psychotherapy.

- Facing the death of a client: What his patient Ellie, who called herself “a pioneer of dying” taught him about facing death.

- Not predicting where the therapy will go: How the therapeutic journeys of his patients often surprises him.

- Taking a detailed history of a recent, 24 hour period: Dr Yalom describes how he uses this intervention to discover surprising information about his patients.

- Brief therapy: His views on whether in-depth psychotherapy is still relevant in this age of brief, solution-focused therapy.

- Giving up hope for a better past: How healing sometimes starts with his clients actually giving up hope for a better past.

- On being creative in therapy: How change and transformation in one of his patients came from working creatively in unexpected ways.

- Effective psychotherapy: His mission to educate and inspire young therapists about what effective psychotherapy looks like.

- Group psychotherapy: His views on the importance of group therapy and positive changes he’s noticing in the field.

Links and resources mentioned in this episode:

- Creatures of a Day: And Other Tales of Psychotherapy (Hardcover) by Dr Irvin D. Yalom

- Creatures of a Day: And Other Tales of Psychotherapy (Kindle) by Dr Irvin D. Yalom

- The Theory and Practice of Group Psychotherapy

Click here to download the transcript of this recording

About Dr Irvin D. Yalom:

Dr. Yalom is Professor Emeritus of Psychiatry at Stanford University and the author of several highly acclaimed textbooks, including Existential Psychotherapy and The Theory and Practice of Group Psychotherapy. He is also the author of stories and novels related to psychotherapy, includingLove’s Executioner, When Nietzsche Wept, Lying on the Couch, Momma and the Meaning of Life, and The Schopenhauer Cure, Staring at the Sun: Overcoming the Terror of Death and his latest book is called Creatures of a Day: And Other Tales of Psychotherapy. Visit Dr Yalom’s website at http://www.yalom.com

Dr. Yalom is Professor Emeritus of Psychiatry at Stanford University and the author of several highly acclaimed textbooks, including Existential Psychotherapy and The Theory and Practice of Group Psychotherapy. He is also the author of stories and novels related to psychotherapy, includingLove’s Executioner, When Nietzsche Wept, Lying on the Couch, Momma and the Meaning of Life, and The Schopenhauer Cure, Staring at the Sun: Overcoming the Terror of Death and his latest book is called Creatures of a Day: And Other Tales of Psychotherapy. Visit Dr Yalom’s website at http://www.yalom.com

Novels and stories by Dr Yalom

- 1974 Every Day Gets a Little Closer

- 1989 Love´s Executioner and Other Tales of Psychotherapy

- 1999 Momma and the Meaning of Life

- 1992 When Nietzsche Wept

- 1996 Lying on the Couch

- 1996 Yalom Reader

- 2005 The Schopenhauer Cure

- 2005 I’m calling the police! A Tale of Regression and Recovery

- 2012 The Spinoza Problem

Non-fiction by Dr Yalom

- 1970 The Theory and Practice of Group Psychotherapy (5th edition 2005)

- 1980 Existential Psychotherapy

- 1983 Inpatient Group Psychotherapy

- 2001 The Gift of Therapy: An Open Letter to a New Generation of Therapists and Their Patients

- 2008 Staring at the Sun: Overcoming the Terror of Death

- 2015 Creatures of a Day: And Other Tales of Psychotherapy

Watch the trailer for the documentary about Dr Yalom called Yalom’s Cure:

YALOM’S CURE – Trailer (English) from DAS KOLLEKTIV on Vimeo.

Transcript:

Clinton Power: This is the Australia Counselling podcast, session number 75. Hello, this is Clinton Power founder of the australiacounselling.com.au. Welcome to another episode of the Australia Counselling podcast, it’s wonderful to have you with us. For this episode today, you’re in for a real treat. The person I’m interviewing today has been an enormous inspiration for me through his writings and his trainings via his textbooks and that person is Dr. Irvin Yalom.

Now Dr. Yalom is professor emeritus of psychiatry at Stanford University and is the author of several highly acclaimed textbooks including, Existential Psychotherapy and my personal favorite, The Theory and Practice of Group Psychotherapy. That was a book that I certainly carried around with me for many years as I was working as a group therapist. He’s also the author of stories and novels related to psychotherapy including, Love’s Executioner, When Nietzsche Wept, Lying on the Couch, Mama and the Meaning of Life, and The Schopenhauer Cure. More recently in 2008 he wrote, Staring at the Sun: Overcoming the Terror of Death.

In today’s interview, we speak specifically about his brand new book called, Creators of a Day and other Tales of Psychotherapy. A very moving a poignant book that I finished reading just recently. We cover a wide range of topics related to psychotherapy in this interview. Dr. Yalom tells us about how his creative writing sits with his practice of psychotherapy. We touch on issues of therapist disclosure in psychotherapy, some of the things he’s learned about death from his patients, and we also talk about some of the important ingredients in therapy. There’s a number of interventions Dr. Yalom uses, which we talk about, and I find that they are very interesting and something I’m wanting to implement myself.

We talk about a number of the cases he mentions in this book, including how we can help our clients with the idea that change may come from actually giving up hope and other unorthodox strategies and interventions you can use in therapy. I hope you’re really going to enjoy this interview with Dr. Yalom. If you’d like to access the show notes where we have links to all the resources we mentioned, just go to australiacounselling.com.au/session75. That’s 75 and counselling spelled with 2 Ls. Without further adieu, here is Dr. Irvin Yalom.

Hello, this is Clinton Power from Australia Counselling and it’s my great pleasure to be speaking today with Dr. Irvin Yalom, who is professor emeritus of psychiatry at Stanford University. Hello Dr. Yalom, how are you today?

Irvin D. Yalom: I’m just fine thank you. It’s a beautiful warm day in California today.

Clinton Power: Is it ever not a beautiful day in California? Today, we’re speaking about your new book, Creatures of a Day and other Tales of Psychotherapy. I must say out of the gate, I found this book very moving and poignant. The description in the book says this book is about your patients that are grappling with life’s 2 greatest challenges; that we must all die and that each of us is responsible for leading a life worth living. I’d love you to tell us about how did you come to write this book and how does your creative writing sit with your practice of psychotherapy?

Irvin D. Yalom: Well, I’m always writing one book or another, so it just was this book’s turn. The last book I wrote I think before this one, I guess, was a novel. Yeah, it was. Then I’ve decided I’m really getting too old now to write any more novels. I really loved doing that, but to write a novel you’ve got to have a really good memory. You’ve got to know what you’ve said in the last several chapters so that you’re not repeating anything. I’ve decided that short stories may be my best form right now. I don’t think you see very many writers writing novels in their 80s or so if you notice that. The stories, I have a way of a huge file in which I put ideas for incidence of common therapy that may be useful for a story. I just start browsing through those files. It’s many, a hundred pages or so. Then I just keep reading it and reading it until some story, some idea, some actor is throbbing with a bit of energy. Then the story, once I select a story, the writing itself is great fun and it comes fairly easily.

As I’ve gotten older though, the space between the stories is getting longer and longer. These are meant to be teaching tales, as are all my stories and all my novels. I’m a professor. I’ve been a professor all my life, so I’m basically a teacher. Even though the general public reads a lot of these stories and novels, I have my secret target audience is always the young psychotherapist. That’s who I’m writing for. I mean the stories to be educational.

Clinton Power: Now wonderful. I have to say, Dr. Yalom, that throughout this book I felt touched particularly by your honest disclosures in the here and now with your patients. I’m thinking of one case in the book, Charles, in the chapter on being real. You quickly correct your therapeutic responses just as the session ends and he’s walking out the door and suddenly disclose in a very real way, a very real disclosure of what you’re experiencing in that moment. I’d love to hear more about how important do you see therapist disclosure in psychotherapy?

Irvin D. Yalom: Well, I think it’s paramount that the therapeutic relationship be very firm, be very authentic, be very real. We’ve known this for a long time, actually since the beginnings of any kind of research into psychotherapy from the work of Carl Rogers, the research psychologist. He wrote, and very convincingly so, of the primary importance of the therapeutic relationship. He elaborated certain factors that were present in good therapists who had effective outcomes. Being genuine and accurate empathy, and then positive unconditional regard. There must be at least a thousand PhD dissertations, a ton of evidence about this.

I am interested in keeping that therapeutic alliance very firm and I tend to be real to my patients. I want this to be a real genuine relationship, not a relationship that’s going to extend outside of therapy. We know that it has certain boundaries, but I tend to be very honest and I tend to be disclosing if I think it will be useful for therapy.

Clinton Power: Yes. A number of your patients were either facing death or close to death, terminal in some way. I’m thinking particularly of Ellie who actually died as you were writing her story.

Irvin D. Yalom: Yeah.

Clinton Power: You recognized in some way that you had not truly connected with the wisdoms in her letters you were writing to each other after each session. Can you tell us, what did you learn about death from Ellie who I think, I believed she called herself a pioneer of dying?

Irvin D. Yalom: Yes, she was a pioneer of dying for her whole friendship client in a sense in her family, she felt she was the first one. What that was implying, it’s a very important thought because I think that … I’ve worked with a lot of dying patients. I always do. Even now, I see 1 or 2 patients in my practice have some kind of fatal illness. I feel like I can be helpful to them. One thought that a lot of my patients have found that even at the very end of their life, they can still offer something. They can still offer some meaning to something or they can model. Others have told me, they can model facing death to their children and their friends. That’s what Ellie meant by being that.

Also, the other issue is that it’s hard to work with people who are facing death. I held back from Ellie and I have to catch myself at that and try not to be a little overwhelmed by it. I know that when I started to work with her, I was writing a textbook called, Existential Psychotherapy, and I decided I knew that a large part of that textbook would have to be how we deal with the anxiety, the primal anxiety, coming from facing death. I started working with a lot of patients with not only metastatic, but terminal cancer. I know after awhile, I began to feel rather shaky. I was having nightmares, trouble sleeping, a lot of anxiety. I went back into therapy at that point.

I realized that the more traditional psychoanalysis that I had, 700 hours of it, there was not a mention of this. This time I chose to go back into therapy with someone who is more existentially oriented and I saw Rollo May for 3 years. Ellie recaptures a lot of that in there. She’s also an extraordinary word-smith, a really good writer and so I like to quote a lot of her messages because they’re so powerful and to evocative.

Clinton Power: Yes. I believe Ellie wanted really to get the message out to the public. She even asked that you would use her real name, is that correct?

Irvin D. Yalom: The only patient I’ve had who really stressed that. She said use her real name and I did, but I didn’t use her last name. I thought that might not be … I don’t know. I didn’t want to run that by the family, so I just used the first name, but I promised her that I would do that.

Clinton Power: I think as psychotherapists, one of the predicaments we often face is well one, not knowing where the therapy will go and then also wondering what happened to our patients. I think you framed this so eloquently in these tales. I’m thinking of the case of Alvin where you ran into him years later after therapy had ended at a memorial service and found out that he had really undergone a transformation after your final session.

Irvin D. Yalom: Right.

Clinton Power: What do you see are the important ingredients in therapy because it seems even through your tales that sometimes the most inconsequential things can be the agent of change?

Irvin D. Yalom: I find that to be more and more true as I keep on working. What’s important is we establish a certain kind of relationship with a person and people will draw out of that relationship, they will draw things that will help their healing in ways that we could never predict. Alvin was a prime example of that. There’s another example of that in the title story, Creatures of a Day, that’s a quotation by Marcus Aurelius and that was a saint. He was taking about evanescence, talking about transiency and we are but creatures of a day, talking about how short-lived in a sense that we all were. I view it as a hair-brained notion, but I was reading Marcus Aurelius and enjoyed it and there were 2 of my patients who I thought would really get something out of reading Marcus Aurelius.

That story is about that notion. What happened was that each of those patients took something that was very real, very important out of Marcus Aurelius, but it wasn’t what I thought they were going to take out of it, not why I gave them the book to read. They drew out of it what was really important for themselves. I’m always surprised by that and if any of you have the chance to see your patients after you’ve stopped therapy or hear from them, maybe many might drop you an e-mail or something, I’m very interested in what they have to say. I will write them back and I’m wondering looking back on things, can you say anything more about what was helpful? It’s a way we keep on educating ourselves.

Clinton Power: Yeah, well it seems that even when we step outside the norms of therapeutic relationship, that some of that magical stuff happens. I’m also thinking of the story of Justine and a former patient of yours, Astrid, who had died, and just how you worked so creatively with her towards the end and how powerful that was for her. Can you say a little bit about that work you did with Justine?

Irvin D. Yalom: That was the nurse, right?

Clinton Power: Yes.

Irvin D. Yalom: Yeah, yeah. This was a woman who had given a whole lot to my patient, but she herself was in great despondency about a son that she had had that was, she feels sociopathic from early life and ended up in San Quentin. She was in great despair and I thought she had lost sight of another part of herself, the part that has given so much to so many patients. Then I did a thought experiment with her. I just asked her if she could imagine a line of patients stretching out of my office who she had really been terribly helpful for. If she could imagine this line going all the way down and around the block and if she could picture each of them. It was very moving experience for her, self-affirming, trying to help her get over the guilt of her son’s life and her feelings of guilt for not having given her son somehow what he needed.

Clinton Power: Dr. Yalom, another intervention which struck me in the book, is that you often take a detailed history of a recent 24 hour period. It seems that this strategy often uncovers some really surprising information about your patients. I’m thinking Alvin as well. You discovered he had very little intimacy in his life from asking about that. Tell us a bit about how you use that in your work.

Irvin D. Yalom: Well, I use it for every single patient I see, often in the very first session. I’ll take 10 minutes and just take them through 24 hours and ask them to pick an average day. I usually start with their sleep, what time they had gone to bed. Then that gives me an opening into what their sleep is like and then what their dreams are like because I do like to use dreams in my work with them. I’m already flagging about my interest in dreams. Then I’ll just dig through all of it, but what I’m really interested for, what I’m fishing for in this is that I want to see how they touch other people in their lives. Who do they have conversations with? Who have they talked to? What kind of friends do they have? How much time do they spend? Who do they take their meals with? All this information which tells me a lot about their interpersonal life and how connected are those parts for the patients, how often, how unconnected and how lonely they are.

Clinton Power: Now I think I read somewhere you had considered calling this book, The Art of the One-Shot Consultation, is that right?

Irvin D. Yalom: There were several here who were one-shot consultations. I thought about that, but then there are some others that were longer therapy, but for awhile. I’m doing briefer therapy now because of my age. I’m not quite sure how long I’ll stay in practice, so I work for a maximum of 1 year. A lot of people consult with me, just they want a single consultation. They may come from some other part of the world and they’re dropping in to San Francisco. I’ve gotten used to a one-shot consultation and sometimes I’ve felt I’ve really done an awful lot for them.

Clinton Power: Well, I’m wondering with symptom-focused, quick fix short-term therapy, is that it seems to be increasingly popular with governments and sometimes even therapists and clients. What are your thoughts on whether in-depth psychotherapy is still relevant?

Irvin D. Yalom: Well, I feel that it’s very relevant to me. There are some patients who can benefit with very, very brief therapy. I feel that the patients that I see for a year, many of them are finished, many of them I may want to send on for further work. I’m very concerned about the very, very brief therapy that’s mandated, at least in my country, by insurance companies. The CBT, which is so impersonal and manual driven and patients’ therapists no longer know how to really relate to their patients and lose so much of what they could have really offered them.

Yes, I do try to work in-depth with patients. I’ll work with dreams. I’ll try to move the patient deeper every session. I stress to patients, another thing I tell people in the first time I see them is that it’s going to help therapy if you can take a risk each session. They understand what I mean, but if they don’t then I say, it’s something that feels hard to tell me. Maybe something you’ve haven’t told to other people. If you say that to people in the very beginning, you have a power later on in your therapy because there will always be times when there’s a session that doesn’t seem to be going anywhere, in which you don’t know what’s happening, and there seems to be a lot of resistance.

Then I can always call their attention back to that. Remember what I said in that first session about taking risks? What’s happening today? How much of a risk have you taken today? You can look at at. Was there a time that were constantly taking a risk here? When was that? I’ll go and dissect the sessions before in terms of risk taking. When I’ve made it really clear to them that it’s going to be helpful to them to take risks.

Clinton Power: Yes and Dr. Yalom, I’m reminded of the chapter, You Must Give Up Hope For A Bit Of Past with Sally. She took a very big risk with you. She was a writer who had been writing, I believe, for about 42 years, but all her writing was sealed in boxes no one had ever seen. She hadn’t had anything published. That seemed like quite an important idea to that client, the idea that not only in taking a risk, but that in some way, she needed to give up hope for a better past. Can you say something about that notion?

Irvin D. Yalom: Yeah. Well, that’s not my original phrase. I heard it from someone else. I don’t quite know where. The idea of giving up the hope for a better past. You have to somehow, I know it seems silly, but there are people who keep having that hope and they keep working on this and I try to help them understand that in trying to help them see their parent’s life. Their parents may have been passing on something their parents got from their parents. My job with you is to help you break that cycle and you have to break the cycle of continuing to blame your parents and continuing to blame your early life. This patient was a particularly fascinating patient for me, that she had all the writing that she had done locked into a huge box in which she can … There’s a second box that she was working on, her more recent writing. In addition to that, she was a superb writer. Then finally, she arrived in my office one day with the box and we opened it together. That story is very accurate and it was fine with her. I ran it by her. It happened very much the way that I wrote it.

Clinton Power: Yes. I’m also thinking of the first chapter in your book, The Crooked Cure with Paul, and that was a very interesting … I believe that was just one session wasn’t it? It had an interesting …

Irvin D. Yalom: That’s all he said he could afford or wanted.

Clinton Power: It seemed to be a great example of, you almost didn’t have any idea where the therapy was going in that one session, is that right?

Irvin D. Yalom: That’s right. I didn’t quite know what he wanted. He wanted something from me that he felt was strong and I could give it to him. The title of that comes from The Crooked Cure. That’s a phrase of Freud’s and he meant by that that there’s a cure that people get, the real cure, which is the cure through psychoanalysis and through transference. Working through transference means working in-depth through your feelings about your early life and your parents. That’s the real cure.

There are some patients though however who don’t do this. They get cured if you will. They get relieved of symptoms through something else that therapists can offer them and that was what happening with this patient Paul. He got the crooked cure from me, but it was all that he really wanted and he was grateful for what happened. It was a total surprise to me and I left the therapy with him very curious about what it was that actually he had gotten from me.

Clinton Power: Yes. Dr. Yalom, I’m thinking early in my training when I was training to be a group psychotherapist that your seminal book, The Theory and Practice of Group Psychotherapy, was very important to me. That was my Bible. I’d love to hear your thoughts briefly on where you see group psychotherapy is today. I know in Australia, unfortunately it doesn’t seem to be offered by many therapists, but I’m wondering if you still see the …

Irvin D. Yalom: I’ve heard that. I’ve had some patients who I’ve seen by Skype therapy in Australia and I would really love them to be in groups. I’ve been astounded that they say there’s just so little groups in the town that they’re in or the city they’re in. That’s just striking to me. I have a very strong feeling about the efficacy of groups. It’s a very powerful kind of therapy. I don’t like what’s happening in the United States about that either because again, because of the economy and because of insurance companies limiting the number of sessions that can be had. I have a therapist that I’m supervising from Germany and they have a very enlightened program where every German citizen can be seen for 2 years in a therapy group and the therapist is well rewarded by the government financially.

There are 2 kinds of therapy that I was very interested in earlier on in my career and one of them was group therapy and the other was conjoined family therapy. For some reason both of them, almost at least in my part of the country, seemed somewhat out of style. I find it difficult at times to find people to do conjoined family therapy. I studied for a year with Virginia Satir. That too is an effective form of therapy and there are some patients that I have who I would just love to have their whole family be seen. Sometimes I can find a therapist who will do that.

A lot of training for therapy is occurring in groups. That is one thing that I do notice. The psychiatric residence, for example, at Stanford and also in 2 other university settings in San Francisco, in their training, they are in a process group. By a process group I mean by that a group which examines its own process, it’s own interaction. It’s a group that is working on the here and now, rather than historical material from each member. Also in counselling programs in my area that in their first year, the students are always in a group of their peers and focusing on their relationships with others. That’s a very good thing. I would just like that there be more therapy groups available and I do whatever I can. I spoke recently at a group therapy meeting. At Miras, we want to start a new association there, so I’m glad to donate the time to that.

Clinton Power: It certainly seems we have some work to do in Australia to rectify that situation. You mentioned earlier that much of your writing, the underlying mission is to educate and inspire young therapists about what effective psychotherapy looks like. Where do you see the future of psychotherapy going in the years and decades to come?

Irvin D. Yalom: Usually when … I didn’t have this conversation with you, but often when I speak to potential interviewers, I say don’t ask me that question. I don’t know. Because right now I’m not teaching anymore at Stanford. I have a very small practice right now. I don’t want to see more than 2 or 3 patients a day. I spend a lot of my time writing. I’m not looking at the country at large or following the literature very much. Certainly, I feel there’s a real shortage of training of people who can work in-depth, right? If I want to refer a patient to a therapist who does deeper work, I’ve got to find someone with grey hair because the more recent therapists often aren’t trained very fully.

That said, I do see a pendulum swinging back. For example, with our psychiatric residents, there was a time a few years ago that they were very little interested in psychotherapy and they were just being trained in their medication. In the last 3 or 4 years, the residents have been asked to meet with me and I have evening seminars at my house. They’re eager to learn psychotherapies and I consider that a very good sign.

Clinton Power: It is a wonderful sign. Sadly, if nothing else from your book, Creatures of a Day and other tales of Psychotherapy, I think this book really speaks to the efficacy of psychotherapy. That’s what I certainly took from it and I’m sure readers will take from it, that psychotherapy still has a place. It is a place where people can go to transform and change and to heal. I’m imagining that was part of the message as well you were wanting to convey. That there is place for psychotherapy.

Irvin D. Yalom: Yeah. If you can ever form some kind of corporation or group to educate group therapists there, I would be very willing to suggest colleagues. I have a couple of my colleagues who went over to China and formed a group therapy institute and trained Chinese therapists to be supervisors themselves. There’s a large group therapy movement there. I’m sure if you need some input, I can suggest some very good teachers to come over and start helping train people there.

Clinton Power: Well, that’s wonderful. Thank you for that very generous offer. I really appreciate you giving up your time Dr. Yalom today. I know you’ve been an inspiration certainly to me and thousands of therapists across the globe. Wishing you all the best with your book, Creatures of a Day, and I hope we can speak again sometime.

Irvin D. Yalom: I hope so. Thanks very much for thinking of me.

Clinton Power: Bye for now.

Irvin D. Yalom: Bye, bye.