According to Eston and Buss (2007), humans engage in sex for a number of reasons including genetic and social dispositions to procreate as well as physical motivations, goal attainment, emotional empowerment, security, spiritual/religious beliefs and personality traits. Paterno & Jordan (2012 p.258) define unprotected sex as “engaging in sexual activity without the use of a method to prevent pregnancy and/or sexually transmitted infections”. Reasons for unprotected sex include biological imperatives, risk-taking, pregnancy ambivalence, relationship strengthening, lack of contraception or knowledge of and cost of contraception, lack of negotiating power, significant and/or heightened sexual desire (Foster, Higgins, Biggs, Holtby & Brindis (2011). As will be proposed in this article, unprotected sex may determine a number of results, bordering between the very positive (planned pregnancies, increased intimacy) and the very negative including unplanned pregnancies and sexually transmitted diseases (STD’s) (Burdette, Haynes, Hill & Bartkowski 2013).

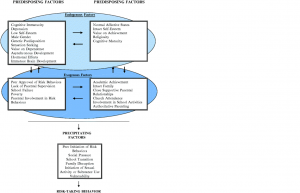

Because of the wide variety of factors involved in unprotected sex, the biopsychosocial (BPS) approach would be the most relevant in determining “the why of unprotected sex” as it contains behavioural, belief, coping, stress and emotional pain elements (Hughes 2003). BPS demonstrates the links between health behaviours and outcomes, with social factors including employment, income and education as well as well as gender, social positioning, cultural beliefs, family orientations and living environments playing their part. The interplay between genetic and psychological dispositions with the above-mentioned factors also provides a strong case for a BPS approach (Braveman & Gottlieb 2014). Social and genetic factors behind unprotected sex have been clearly established (Hughes 2003). Suls and Rothman (2004) indicate that recent advances in health psychology in terms of research and treatments can be attributed to the BPS model and thus BPS is necessary for one to gain a holistic insight into the domain of unprotected sex. Samenow (2010) also argues that the BPS model is highly relatable to issues such as sexual addiction because it allows for a wider picture of individual problem sexual practices and thus plans for treatment can be devised addressing the many factors influencing one’s sexual addiction.Halkitis, Wolitski & Millen (2013) espouse BPS in understanding biological, behavioural and psychosocial factors involved in male to male unprotected sexual encounters. The following table “Factors contributing to the onset of risk-taking behaviours during adolescence” (Irwin & Millstein 1986, cited in Sales & Irwin 2013) is an example which highlights the complex mix of variables involved.

From a biological evolutionary aspect, humans have evolved to copulate in order to procreate and throughout our history as a species, this is what we have done (Fisher 2000). Holloway and Wylie (2015) describe this need to engage in sex as sex drive, which “describes the biological need, encompassing both anatomical and neuroendocrine-physiological responses to sexual thoughts or stimuli” (p. 224). Buss and Schmitt (1993) state that sexual activity and strategies have evolved so that matings can occur where reproductive benefits are higher than any costs associated with it. Interestingly in accounts provided by participants in a study on unprotected sex by Siegel, Meunier & Lekas (2017), biological drives were used as a justification by both men and women who suggested their impulsiveness was linked to a powerful and unmanageable sex drive. Aaarsen (2007) also suggests that because as humans we have knowledge of our own mortality, we are attracted to the concept of leaving a legacy via our offspring. Males, in order to maximise the chances of this legacy have traditionally learned to control women’s sexual activity and fertility through suppression and by acquiring multiple sex partners through such behaviours as having concubines, polygamy, mistresses, rape and ensuring that partners were continually pregnant. Buss and Schmitt (1993) state that traditionally in the case of women, the needs have been more based on the quality and quantity of resources that men can provide for them and their children, particularly in the long term. In both sexes, differing psychological systems and behaviours have been activated in order to create solutions to reproductive challenges (Meston & Buss 2007). In the case of sexual addictions, Samenow (2010) highlights the ABC (Amygdala, Behavioural reward and Cognitive) model of impulse control as having a relationship with hypersexual behaviours observed in affective disorders which are “triggered by stress, preoccupation and reward from engaging in sexual behaviour, and continued behaviour despite negative consequences” (p. 71). Omori & Ingersoll (2004) state that adolescent biological maturation has psychosocial consequences regarding personal values, cognitive scope, social environmental and self-perceptions. These consequences are mediated by risk perception and peer group characteristics. Omori and Ingersoll (2004) cite studies in which egocentrism and low self-concepts have been related to higher risk behaviour. (McCaulley, Shadur, Hoffman, Macpherson & Lejuez 2015) raise another bio/psycho issue where adolescents with elevated “Callous Unemotional” traits are more likely to engage in risky unprotected sex. In the case of male to male unprotected sex, Wolitski & Millet (2013) suggest that whilst the biological efficacy of HIV transmission is biologically determined, behavioural decisions substantially increase the risk of infection.

The role of social structures such as human religious belief systems are also interrelated with a biological understanding and impulse towards procreation. All major religious traditions provide guidelines for sexual beliefs and behaviour and their influence extends into almost every country in one form or another (Arousell & Carlbom 2017). Reuther (2008) describes the traditional role of the Catholic Church from the times of St. Augustine and Aquinas in promoting the idea that sex is inherently sinful, and only allowed in heterosexual marriages for the purposes of procreation. The modern Catholic church maintains the primacy of “sex for babies” and uses its influence in many countries to pressure governments against the teaching of sexual education and family planning. Whilst the power of Catholicism has waned in many Western cultures, in some countries such as the Philippines, its influence comes in the denial of sacraments for those who use contraception and in extreme cases such as in warfare, denial of emergency contraception, even in cases of rape (Reuther 2008). Just a visit from a Catholic Pope can influence beliefs regarding unprotected sex, contraception and fertility (Basso & Rasul 2017). In the case of Islam, the links between traditional beliefs and sexual practices are also evident. This is also seen in countries in which Islamic culture comes into contact with Western practices and beliefs. It has been found that sexually experienced Islamic teenagers use contraception less because of social controls exercised by community and social networks. These controls also limit access to sexual health care (Arousell & Carlbom 2017). Nevertheless, it can also be argued that religious devotion can also limit the number of unwanted pregnancies and STD’s because of the espousal of personal conservatism (Miller & Gur 2002 & Semenow 2017).

As previously mentioned, an aligned issue with unprotected sex is risk taking which can be defined as “engaging in behaviours that may have harmful consequences but simultaneously provide an outcome that can also be perceived as positive” (Sales & Irwin p.13). Adolescence is a time associated with risky sexual behaviour, characterised by greater numbers of sexual partners and limited use of condoms during sexual intercourse. In a study on homeless youth in Canada conducted by Chen et al. (2016), it was found that excessive alcohol and drug use lower inhibitions for sexual activity. Brady, Gruber & Wolfson (2017) point towards a number of causes of risk taking related to relationship quality amongst young women, which include low agentic self-efficacy for negotiation of condom use. Interestingly they also found that both negative and positive relationship quality can lead to unprotected sex, depending on such factors as levels of trust and dependency. Tucker et al. (2012) found that some homeless girls and women intentionally get pregnant in order to improve their life circumstances. Mc Cauley et al. (2015)and Sales & Irwin (2013) also targeted the role of poor parenting where lack of protection knowledge was evident as well as low levels of parental supervision and monitoring. Even more extreme risk taking is highlighted by Halkitis & Parsons (2003). They discuss the term “barebacking” which is defined as “intentional unsafe anal sex” (p. 367). Men participate in barebacking for a number of reasons including the success of medical treatments for HIV, sensation seeking, need for exciting and novel sex, availability of compulsive and anonymous sex via the internet and affirmation of physical attractiveness.

Whilst adolescence is often mentioned when it comes to sexual risk taking, adults are not averse, for example older men who seek out younger partners or who take anti-impotence drugs may put themselves and others in danger (Jurberg 2009). Society and culture also impact on risky behaviour. Mengo, Small, Sharma & Paula (2016) mention the various cultural factors influencing sexual risk taking. Women’s ability to gain and control resources and to be involved in family decision making, to control the use of contraception and have access to health services is relevant to both the country and area that they live in. Other issues such as the stigmatism of HIV and its transmission in parts of Africa as well as early marriages in Nepalalso lead to a greater growth of STD’s through unprotected sex. Social and structural influences have been shown to be associated with male to male unprotected sex, demonstrating the links between discrimination, bullying, abuse and rejection to poor health outcomes(Wolitski & Millet 2014). Paterno & Jordan (2011) also mention that within the United States issues such as race, levels of income, employment status and education all impact on unprotected sexual activity. In the case of women, violence and physical, verbal, psychological and sexual abuse also are also determinants.

Working on a premise that biological education can increase knowledge of reproductive physiology, and therefore decrease unwanted pregnancies, sexually transmitted diseases and abortions, Hadjichambi et al. (2016) have demonstrated that inquiry based interventions within classrooms may provide some answers. Chapin (2000) also argues for education on the role of mass media’s influence on adolescents’ beliefs and practices regarding sexuality.Tucker et al. (2012) suggest improvements in living conditions and education for homeless youth would reduce the high rates of STD’s and abortions. Likewise, Wolitski (et al. (2013) suggests environmental and social factors need to be addressed when working with the disparities in male to male sex infections.Siegel (et al. 2017) argue for education which debunks cultural beliefs being used as excuses for unprotected sex. Aroussell & Carlbom (2016) suggest better understanding of cultural sensitivities and the use of person centred care as effective strategies in dealing with Muslims living in Western cultures regarding reproductive health. Cheng et al. (2016) believe that evidence based and youth centred addiction treatment may also help to prevent risky sexual practices. Foster et al. (2011) recommend further studies based on ethnic and racial influences in determining contraceptive choices. Likewise, Mengo et al. (2016) suggest future studies focused on traditional gender roles which impact on Women’s ability to negotiate and make choices for safe sex.

Author: Peter Robin

Aarssen, L. (2007). Some Bold Evolutionary Predictions for the Future of Mating in Humans. Oikos, 116(10), 1768 – 1778

Arousell, J., & Carlbom, A. (2016) Culture and religious beliefs in relation to reproductive health. Best Practice & Research Clinical Obstetrics and Gynaecology, (32), 77 – 87.

Bassi, V., & Rasul, I. (2017). Persuasion: A Case Study of Papal Influences on Fertility-Related Beliefs and Behavior. American Economic Journal: Applied Economics, 9(4), 250-302

Brady, S. S., Gruber, S. K., & Wolfson, J. A. (2016). Positive and negative aspects of relationship quality and unprotected sex among young women. Sex Education, 16(6), 586-601.

Braveman, P., & Gottlieb, L. (2014). The Social Determinants of Health: It’s Time to Consider the Causes of the Causes. Public Health Reports, 129(2), 19–31.

Burdette, A. M., Haynes, S. H., Hill, T. D., & Bartkowski, J. P. (2014). Religious Variations in Perceived Infertility and Inconsistent Contraceptive Use Among Unmarried Young Adults in the United States. Journal of Adolescent Health, 54, 704-709.

Buss, D. M., & Schmitt, D. P. (1993). Sexual Strategies Theory: An evolutionary perspective on human mating. Psychological Review, 100(2), 204-232.

Chapin, J. R. (2000). Adolescent Sex and the Mass Media: A Developmental Approach. Adolescence, 35(140), 799 – 803.

Cheng, T., Johnston, C., Kerr, T., Nguyen, P., Wood, E., & DeBeck, K. (2016). Substance use patterns and unprotected sex among street-involved youth in a Canadian setting: a prospective cohort study. BMC Public Health, 16(4) 1 – 7.

Fisher, H. (2000). Lust, Attraction, Attachment: Biology and Evolution of the Three Primary Emotion Systems for. Mating, Reproduction, and Parenting. Journal of Sex Education & Therapy, 25(1), 96 – 104.

Foster, D., Higgins, J., Biggs, A., McCrain, C., Holby, S., & Brindis, C. (2012). Willingness to have unprotected sex. The Journal of Sex Research, 49(1) 1 – 7